DWAIN ESPER: A VERY CREEPY FILMMAKER INDEED

A genius of exploitation? A tasteless filmmaker? A con man? Dwain Esper is certainly one of American cinema’s best kept secrets. While Tim Burton in 1994 gave Edward D. Wood Jr. his consecration as the worst director of all time, and elevated his name as the ultimate B-movie auteur, Dwain Esper’s reputation lurks menacingly behind his. Yet, he surely is one of the creepiest figures in cinema history.

A genius of exploitation? A tasteless filmmaker? A con man? Dwain Esper is certainly one of American cinema’s best kept secrets. While Tim Burton in 1994 gave Edward D. Wood Jr. his consecration as the worst director of all time, and elevated his name as the ultimate B-movie auteur, Dwain Esper’s reputation lurks menacingly behind his. Yet, he surely is one of the creepiest figures in cinema history.

Dwain was part of a group of filmmakers who got around the strict American censorship production code that sought to purify cinema from its promotion of evil ethics and sexualised images. These filmmakers not only often went around the US exhibiting their own films, but also slid past the code by claiming themselves as educators. For instance, a film about explicit drug use would be preceded by patronising title cards that said ‘this film was made to show the horrors of opium. We must do something!’

Of course, the audience would not go to these films to be educated, and Esper knew that well. Born in Washington State in 1893, he became a filmmaker by accident after a long career in the carnival business. The gypsy life he led is what brought him and his wife together. Hildegarde Stadie was in fact the niece of a patent medicine peddler and as a little girl travelled all over the country to help her uncle sell their cure all tonic. Famously, part of the presentation included a too young Hildegarde appearing nude with a python draped around her shoulders.

Dwain met Hildegarde, fell in love, married her and the two became the most damned sanctified couple in the history of exploitation cinema. He directed the films, and she wrote them. Their collaboration began in the 7th Commandment (1932), the story of an adulteress. The film is unfortunately lost. The next collaboration is perhaps their best. Narcotic (1933) is a highly sexualised story of an opium eater that was apparently inspired by Hildegarde’s own uncle.

Dwain met Hildegarde, fell in love, married her and the two became the most damned sanctified couple in the history of exploitation cinema. He directed the films, and she wrote them. Their collaboration began in the 7th Commandment (1932), the story of an adulteress. The film is unfortunately lost. The next collaboration is perhaps their best. Narcotic (1933) is a highly sexualised story of an opium eater that was apparently inspired by Hildegarde’s own uncle.

The film actually doesn’t look too bad stylistically, given the budget and the usually stagey and rushed style. In truth, it looks better than the majority of Monogram pictures. However, it is obvious exploitation. Esper not only shows lengthy sequences of heavy drug use, needles and demoniacally sexually aroused men feeling up women, but also the most horrific medical stock footage of a woman’s stomach being cut up.

This use of medical archive footage would be even more disturbing in Sex Madness, his 1938 film about a woman giving syphilis to her husband, where it is used to portray real life cases of venereal diseases in close detail. A deeply disturbing film, Sex Madness is currently always topping the charts at archive.org, and you can just imagine the disappointment on people’s faces who may expect to see a little trivial vintage nudity in getting a lot more than what they bargained for…

Esper attempted a go at straight up horror. Inspired by a Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cat, Maniac is introduced as yet another education on social taboos and mental illnesses. The film is intensely creepy and dark, even in its use of music, and in the way in which the film’s story and action is broken up by title cards describing the sort of mental illness that the characters on screen are presenting. Some shocking images include a (hope to god not a real life) cat’s head being squeezed until one of its eyes pops out and quite an explicit rape sequence incredibly controversial for 1934, the year in which it was released to a wider audience of naughty, naughty people…

Surprisingly, the film wasn’t as successful. Esper’s audience was after all made of people that wanted to be shocked, and a title like maniac sounded too much like numerous other bold horror productions of the same time. Therefore, he returned to the more explicitly educational theme in 1935 by producing his most famous work, which was incredibly financed by a religious group Reefer Madness also known more patronizingly as Tell Your Children. There is no real story in this film, much like there is no real story in narcotic. It’s just a film about a trio of drug dealers inviting a group of wild teenagers back to their house for a party where their descent into drug abuse begins and their behaviour gets violent and dangerous. Campy as hell, Esper produced the film’s reissue which was actually directed by Louis J. Gasnier.

Surprisingly, the film wasn’t as successful. Esper’s audience was after all made of people that wanted to be shocked, and a title like maniac sounded too much like numerous other bold horror productions of the same time. Therefore, he returned to the more explicitly educational theme in 1935 by producing his most famous work, which was incredibly financed by a religious group Reefer Madness also known more patronizingly as Tell Your Children. There is no real story in this film, much like there is no real story in narcotic. It’s just a film about a trio of drug dealers inviting a group of wild teenagers back to their house for a party where their descent into drug abuse begins and their behaviour gets violent and dangerous. Campy as hell, Esper produced the film’s reissue which was actually directed by Louis J. Gasnier.

However, quite confusingly, he directed his own version of the film in 1936 called Marihuana: The Devil’s Weed. I’m going to go ahead and say that Esper’s wild and amateurish version of the story, from a script by his lovely wife, is actually more fun than the college pot-head cult classic Reefer Madness that can result quite dull a times.

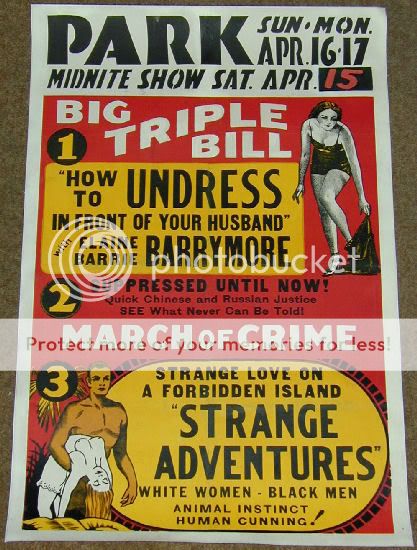

Other films by Esper included a short called How to Undress in Front of Your Husband (1937) about creepy stalking and Modern Motherhood (1934) about a young couple of newlyweds having to decide whether they want to keep living the high life or have a baby instead – as you would.

But Esper’s career went beyond that. He produced re-issues of films in the most outrageous of ways. Splicing footage from early porn into the dull moments of films for no apparent reasons, swindling friends out of money and then charming them to prevent them suing him and bringing Tod Browning’s famous film Freaks on his roadside show without MGM’s consent. He also exhibited a documentary called Hitler’s Strange Love Life (or Will It Happen Again?, 1948) and drove around in a ’37 Mercedes saying it was the Fuhrer’s very own car. Wikipedia also says that he at one point exhibited the mummified body of Oklahoma Outlaw Elmer McCurdy, and in fact this corpse can actually be seen in Esper’s film Narcotic!

But Esper’s career went beyond that. He produced re-issues of films in the most outrageous of ways. Splicing footage from early porn into the dull moments of films for no apparent reasons, swindling friends out of money and then charming them to prevent them suing him and bringing Tod Browning’s famous film Freaks on his roadside show without MGM’s consent. He also exhibited a documentary called Hitler’s Strange Love Life (or Will It Happen Again?, 1948) and drove around in a ’37 Mercedes saying it was the Fuhrer’s very own car. Wikipedia also says that he at one point exhibited the mummified body of Oklahoma Outlaw Elmer McCurdy, and in fact this corpse can actually be seen in Esper’s film Narcotic!

I’m sure there must be plenty of other stories about this outrageously strange and macabre individual and perhaps one day I will look into this sinisterly fascinating side of the most tasteless American cinema. Esper is now something of an underground icon and most of his surviving films are available online as public domain. He is amicably called the King of the Celluloid Gypsies. He died a relatively happy man in 1982.