James Brabazon on WHICH WAY TO THE FRONT LINE FROM HERE: THE LIFE AND TIME OF TIM HETHERINGTON

A report from the screening of the film at the 8x8 Documentary Film Festival, NUIG, Galway

A report from the screening of the film at the 8x8 Documentary Film Festival, NUIG, Galway

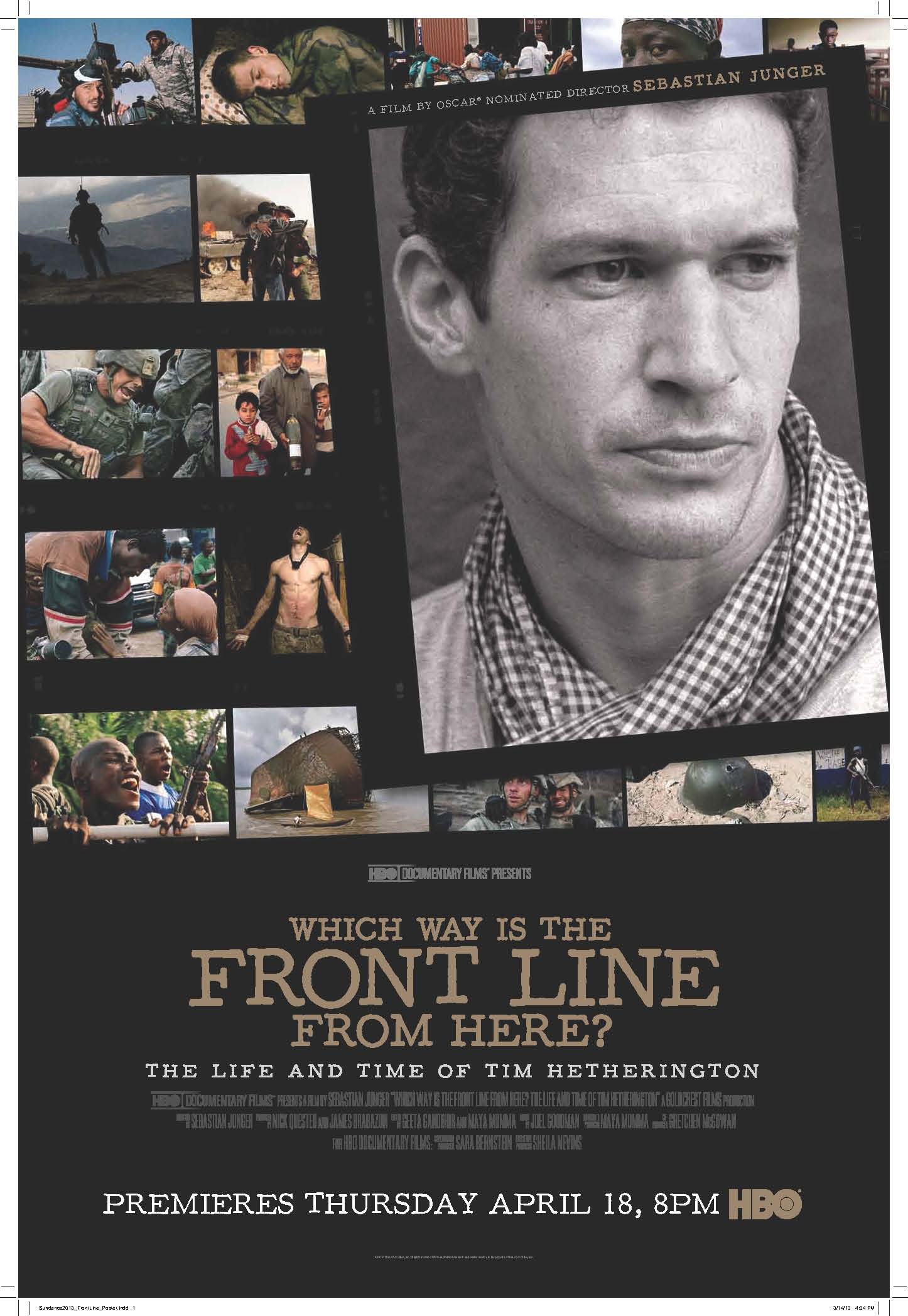

Tim Hetherington was a British photojournalist whose works revolutionised the way people looked at the frontline. His work ranged from videos to still photography, which he shot using many different types of equipment, and closely portrayed in humanity and authenticity violent conflict and revealed a hidden side to war. His career reached a highpoint when Restrepo, a documentary he co-directed with Sebastian Junger, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2011. Yet, just as his reputation and worldwide acclaim peaked, his fearless antics led him to his death in April later that year as he was covering the Libyan civil war.

Friends and colleagues of Hetherington, Sebastian Junger and James Brabazon, decided to honor his life and work with the documentary Which Way is the Front Line from Here. The documentary was screened as part of the 8x8 Documentary Film Festival, a series of week-long documentary film festivals that run back to back across five university campuses across Ireland and presents works which deal with important social, political and human rights issues.

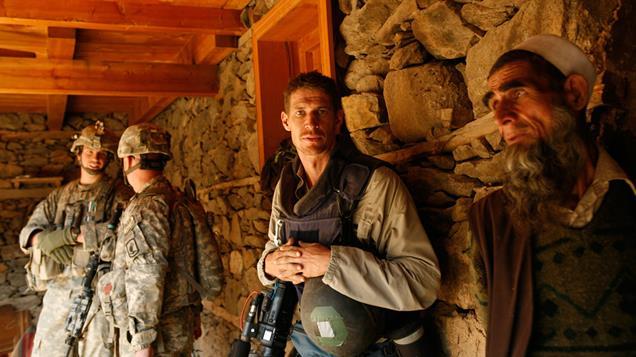

James Brabazon, producer of the film, had also worked with Hetherington in Liberia, where they covered the Liberian Civil War, a collaboration that also resulted in the film Liberia: an Uncivil War (2004) a film he co-directed and on which Tim was the cinematographer. He was present its screening NUIG and took the time to talk about the film, Tim Hetherington and the difficulty and dangers of working as a front line photojournalist.

“The original idea for making a film on Tim came from Sebastian [Junger],” he said. “A lot of people who were with Tim when he was actually killed had gone to New York for his memorial service. He wanted to understand what had happened, both as a friend and as a journalist. He started speaking to the people that came over and was interviewing them informally but also on camera. It became clear that there was a story to be told – as well as a story of Tim, it was a story of what had happened.” HBO backed the project up, after what Brabazon defined the ‘shortest commissioning meeting in history’.

Although there are elements of investigation into what led him to his death, Which Way is the Front Line from Here is more an intimate portrayal of Hetherington’s own personality and a journey of discovery into his motivations for pushing himself to the limit in portraying such scenes of tragedy and violence. “Tim’s work in conflict was very preoccupied with the study of young men and violence,” explained Brabazon. “The things he was battling with in exploring in Libya were very similar from the things he was dealing with in Liberia. He wanted to understand how young men in conflict see themselves and what it is that informs such perceptions in conflict. Tim was fascinated by that feedback. But being in war is like being in a vortex. Tim was a young man too. He too ended up being sucked by that same gravitational pull that sucked those young men into cycles of violence. That is the reason why he went to Libya. There was no reason for him to be there, yet the vortex of violence is so irresistible.”

Although there are elements of investigation into what led him to his death, Which Way is the Front Line from Here is more an intimate portrayal of Hetherington’s own personality and a journey of discovery into his motivations for pushing himself to the limit in portraying such scenes of tragedy and violence. “Tim’s work in conflict was very preoccupied with the study of young men and violence,” explained Brabazon. “The things he was battling with in exploring in Libya were very similar from the things he was dealing with in Liberia. He wanted to understand how young men in conflict see themselves and what it is that informs such perceptions in conflict. Tim was fascinated by that feedback. But being in war is like being in a vortex. Tim was a young man too. He too ended up being sucked by that same gravitational pull that sucked those young men into cycles of violence. That is the reason why he went to Libya. There was no reason for him to be there, yet the vortex of violence is so irresistible.”

The film also deals extensively with the dangers of reporting from a zone of violent conflict and the incredible risks that reporters take. For instance, in his dedication to the search of a perfect, true and genuine viewpoint on war, Hetherington added danger to his work by employing certain unorthodox methods. “When he was shooting with me in Liberia, he was using a Rollerflex, which is a camera with a technology that hasn’t changed since the thirties. At that time he was the only person taking pictures like that in conflict. It’s a slow process with its rolls of paperback film. And when you take a picture like that it means that every picture has to count. You can’t spray and pray like with a DSLR. Shooting like that slows you down, but it also slows down the way you look at the world and reveals another level to the conflict. You see something beyond the surface, which is what makes Tim’s work stand out.”

“Tim is really present in his work. In Diary (2010), he puts himself in his work for the first time. You can see the way he interacts with people. He is a six foot white guy walking around Africa. What you see in this work is a sort of consideration but you also see something of him. His understanding and his passion, which also really comes through in his photography. Looking at his photographs is like looking at compressed solid. It’s all there.”

“Tim is really present in his work. In Diary (2010), he puts himself in his work for the first time. You can see the way he interacts with people. He is a six foot white guy walking around Africa. What you see in this work is a sort of consideration but you also see something of him. His understanding and his passion, which also really comes through in his photography. Looking at his photographs is like looking at compressed solid. It’s all there.”

Brabazon also looked at the ethical and moral problems, which are part of the work of a frontline reporter. “The idea of being a war reporter and being objective or neutral is a lie,” he explained. “It’s impossible. If you work on the frontline especially, there will come a time when you will have to exercise your natural right to self-defence. The point at which you practice that right is the point when you are no longer an observer and you become an active participant. The trick here is to realise that immediately and get over it. What you have to ask yourself is whether or not what you are doing is credible, and that research of authenticity is what drives you and what also drove Tim.”

A photojournalist like Brabazon or Hetherington also has to deal with the inevitable struggle that comes from leading two separate lives. While one life is led in the wealthier and more privileged side of the world, another one is led in constant danger on underprivileged and poverty ridden grounds. This, as Brabazon described, is not a very easy thing to do. “Sometimes, after I come back home from a trip, I find myself through a supermarket absolutely bored by the tyranny of choice. Actually, it once came to me that what the rebels in Liberia were fighting for was the opportunity to be born in a supermarket. There is no great ideology in it. So the fact that you will be able to come back home is a privilege and if you can bring yourself to seeing it that way, then that is a good way of getting through your toughest moments on the frontline.”

Tim Hetherington’s death indeed came to a blow on global photojournalism, and it was a big loss to the art world as well. Junger and Brabazon were directly affected in diametrically different ways. While his friend’s death led Junger to his decision of never working on the frontline again, Brabazon decided that it would have felt like a betrayal to have done so. With his enormous experience of reporting from poor and war zones, which can be sensed through the intensity of his personality and the determination in his eyes, Brabazon looks prepared to continue his work in Syria, which he has been exploring for quite some time.

Yet there was a particular thought that he shared with the audience in attendance, which was particularly disturbing. “If young men didn’t find something meaningful and enjoyable about war there wouldn’t be war. Therefore, if you are interested in stopping or even limiting war, you have to grapple with this essential truth.”